You are here

The disease of seafaring

The disease of seafaring

Sam Chambers July 17, 2025 https://splash247.com/the-disease-of-seafaring/

Steven Jones, the founder of the Seafarers Happiness Index, reports on disturbing deaths at sea figures tallied by the International Labour Organization.

A groundbreaking new report on fatalities onboard ships has revealed that illness and disease are the leading killers of seafarers worldwide. The first standardised global data collection on seafarer deaths, conducted for fatalities occurring in 2023, provides unprecedented insight into the dangers faced by those who work at sea.

Hidden crisis at sea

In 2022, the International Labour Conference approved important amendments to the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC, 2006). One key provision required that all deaths of seafarers employed, engaged, or working onboard ships be investigated, recorded, and reported annually for inclusion in a global register.

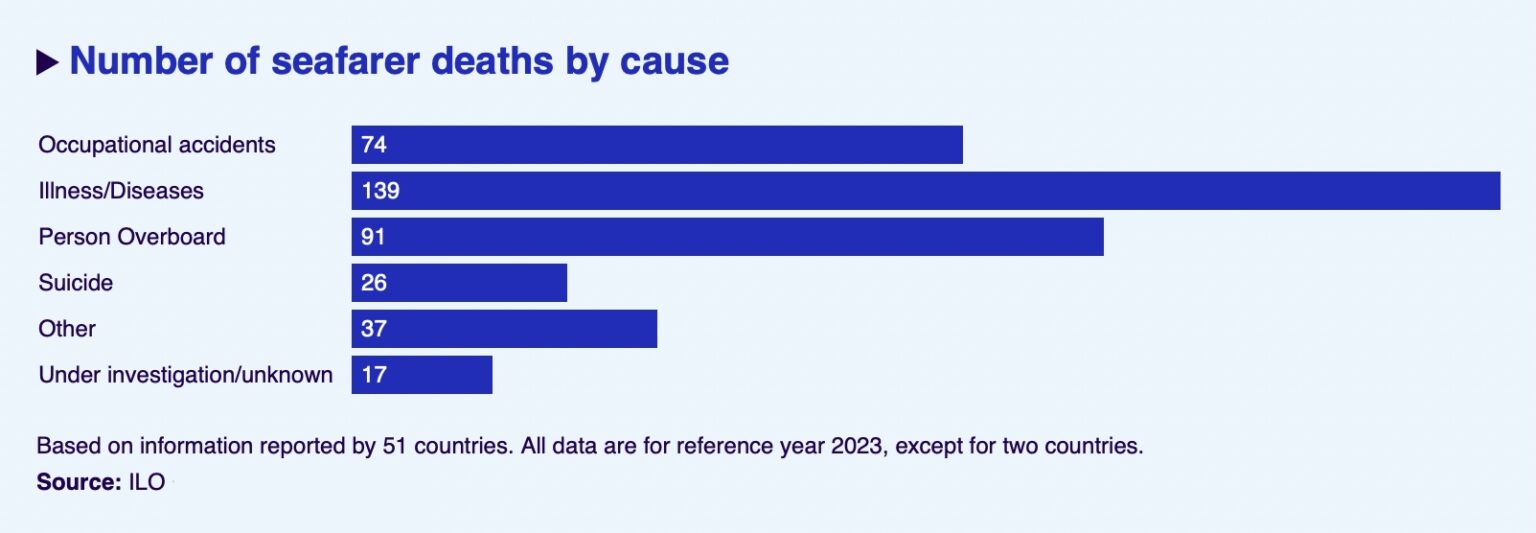

The resulting report provides the first comprehensive look at fatality patterns across shipping. This inaugural experimental data collection phase gathered information from 51 countries and documented 403 seafarer deaths.

The statistics paint a sobering picture: illnesses and diseases claimed 139 lives (34.5%), making them the leading killer of seafarers, outpacing the dangers of falling overboard (22.6%) and workplace accidents (18.4%). This revelation is deeply troubling, exposing the persistent failure to provide adequate healthcare at sea.

At first glance, this might seem unsurprising. After all, cardiovascular diseases and non-communicable illnesses are the leading causes of death globally, with heart disease and cancer dominating mortality statistics in developed nations. Yet the maritime context reveals a disturbing paradox.

What makes this data particularly alarming is the fact that fatalities are occurring despite rigorous pre-employment medical screenings designed to create a healthier, more resilient workforce. When seafarers who have passed medical fitness tests are still dying from preventable conditions at sea, it signals a fundamental breakdown in the system.

When checks are failing

Going to sea has always had its unique attendant dangers, now we can see that it is literally bad for one’s health. If warning signs are being missed before deployment, then even advances in telemedicine, training, and communications cannot prevent the deadly toll that persistent health risks exact on seafarers.

The reality is especially stark as ships often operate in profound physical isolation. When a seafarer suffers a heart attack or stroke at sea, the critical “golden hour” for treatment often slips away before medical treatment can be reached. This remoteness proves lethal. The deaths from health-related issues at sea occur nearly twice as often as those from occupational accidents, while in ports these numbers converge.

Though a ship may boast a “hospital,” the quotation marks tell the real story. Even with expert medical advice and quality equipment, the fundamental limitations of emergency care at sea remain insurmountable, as the figures now show.

Patterns of risk

Then come the compounding risk factors. The fact that shipboard work combines multiple health stressors including physical demands, irregular work schedules, limited exercise opportunities, potentially poor dietary options, and psychological stressors including isolation. As is so often reported to the Seafarers Happiness Index, these issues are a constant for seafarers to contend with.

There is also the small matter of an aging workforce: With 83% of fatalities occurring among seafarers aged 30 and above, age-related health risks are significant and potentially accelerated by the demanding nature of seafaring.

Deck crew represented around half of all deaths, while engine department personnel showed a disproportionately higher rate of suicide. Rank-based vulnerabilities also emerged. With able seamen, comprising nearly half of all rank recorded fatalities.

These statistics paint a stark picture: an able seaman over thirty working on a medium-sized bulk carrier at sea may want to reconsider some life choices, as they face a convergence of the industry’s most serious risk factors, a harsh reality for many working at sea today.

Seafarers represent a uniquely vulnerable population in healthcare terms, hard to reach and seldom heard by medical services. Even when at home, they receive limited preventive care. Extended periods at sea mean seafarers routinely miss regular health check-ups that could identify developing conditions before they become life-threatening.

This creates a vicious cycle of healthcare avoidance. Many seafarers are reluctant to seek medical attention, either preferring not to spend their precious leave dealing with health concerns, or feeling overwhelmed by the appointments they have already missed. This sense of being “behind” on their health often drives them to retreat from care altogether, compounding an already dangerous situation.

Alarming homicide rate

Beyond disease-related deaths and accidents, perhaps most troubling were the 26 suicides, representing 6.5% of deaths and highlighting the severe mental health strain at sea. The remaining fatalities included 37 deaths (9%) from various causes such as natural deaths, alcohol-related incidents, homicides, and deaths occurring ashore, while approximately 4% of cases remained under investigation at the time of reporting.

The homicide risk is hugely chilling. While the exact number of murders is not specified, their inclusion in this category signals a potentially alarming level of violence at sea. For context, homicides typically account for less than 1% of all deaths in most developed nations. Even in countries with higher violence rates, homicides rarely exceed 3-4% of total mortality.

The potential for homicides to represent a significant portion of the “other causes” category raises serious questions about security and violence prevention in the maritime industry. Whether pirates, terrorists or other seafarers there are deadly adversaries in the mix, and this is a frightening and terrifying reality. If even a fraction of these “other causes” are homicides, we are looking at a seagoing murder rate that far exceeds that in general populations.

This seems to indicate a dramatically elevated level of violence that demands immediate attention from flag States, shipowners, and international regulatory bodies. It also needs some degree of reflection from seafarers too.

The report’s categorisation of violence as both “unexpected and unplanned” yet statistically anticipated further complicates the picture. This dual characterisation reflects the complex nature of aggression at sea. Individual incidents may be unexpected, yet the risk factors that contribute to violence (isolation, confined spaces, multicultural crews with potential tensions, limited escape options, security risks) are well-known within the industry.

The findings raise important questions about the role of flag States in seafarer health and safety. The report does not break down mortality by flag, but this is a valuable area for future research. Understanding whether certain flags have higher mortality rates, particularly for violence-related deaths, would help identify regulatory best practices and areas for improvement.

We need transparency when it comes to both life and death at sea, this is a start, but the answers about fatalities bring yet ever more questions, but uppermost is who will fix this?

The ILO report can be accessed here (https://ilostat.ilo.org/blog/new-data-reveals-leading-causes-of-seafarer...)